Appeal to Popularity: Don’t Jump on the Bandwagon

“Be careful when you follow the masses. Sometimes the ‘M’ is silent.”

-Anonymous (perhaps Unanimous)

I had a conversation with my friend, Majority:

Me: “Buying a house is not always the best investment.”

Majority: “Most people want to buy a house, so it must be the best investment. It’s just common knowledge.”

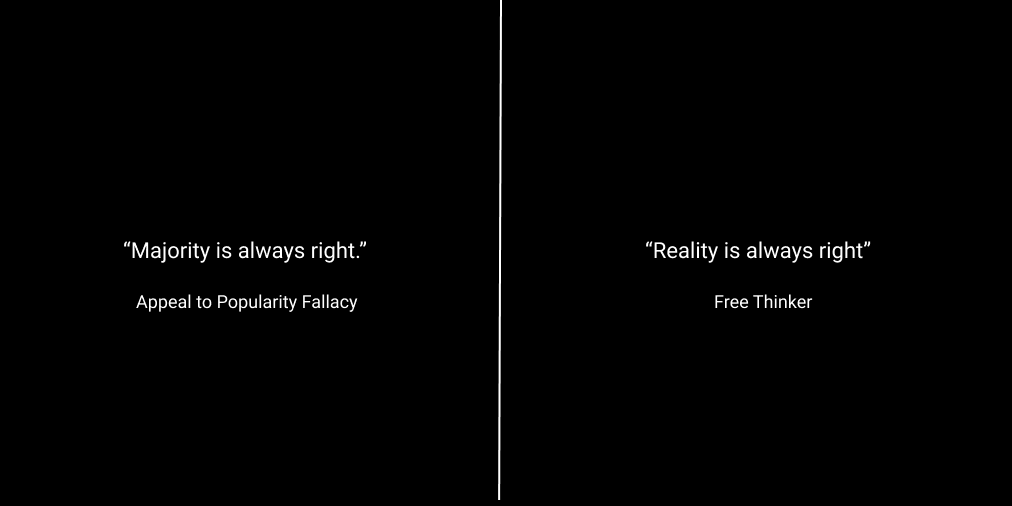

This is an example of a fallacy in informal logic called “Appeal to Popularity.”

What Is Appeal to Popularity?

Appeal to popularity happens when someone makes a claim based on popular opinion or on a common belief among a specific group of people. My friend Majority thinks that buying a house is the best investment because it’s a popular view. Because it’s popular, he reasons, it must be true.

Appeal to popularity is an informal fallacy because the popularity of a claim doesn’t provide evidence that the claim is true. Something is not automatically true if it’s popular. If I believe something, that doesn’t make it true. Likewise, if the majority of the people believe something, that doesn’t make it true.

For example, at one time, everyone believed that the sun orbited the earth, but that claim was false.

Appeal to popularity is also known as the Argumentum Ad Populum, Appeal to the Majority, Appeal to the People, Bandwagon Fallacy, and Consensus Gentium. It is one of the most common logical fallacies along with Ad Verecundiam (aka Appeal to Authority), the Ad Hominem fallacy, and Hasty Generalization. (Note that Douglas Walton discusses a different fallacy that is also called ‘Ad Populum.’)

People are motivated to commit the fallacy because of the bandwagon effect. The bandwagon effect is a cognitive bias. Humans are social animals, and it is common for them to fall for popular beliefs. We have psychological tendencies that promote group living. It’s easier to live in a group if you share the same beliefs as most people in that group, so humans evolved a tendency to believe what most of the people around them believe.

Here’s how the appeal to popularity fallacy looks:

Everyone thinks that X.

So, X must be true.

When someone uses the appeal to popularity fallacy, they will cite a belief that many, most, or all people hold and claim it to be true. This is a fallacious argument because, as we’ve seen, the majority opinion doesn’t always translate into truth. The majority of people can believe something false.

There's a difference between truth and belief. You can believe things that are false, and you can disbelieve things that are true. The number of people who believe it doesn’t matter. To be true, a claim has to match how the real world is. It’s not enough for people to believe it.

Because the truth is different from belief, citing what people–even the majority of people–believe is irrelevant to evaluating a claim’s truth or falsity. That’s why ad populum is categorized among the fallacies of relevance: it appeals to irrelevant information in an effort to get you to endorse a claim.

Here are some more examples of appeal to popularity:

Example #1

“Most people believe that there is life after death, so there is life after death.”

Example #2

“Most people no longer believe that there is life after death, so there is no life after death.”

Example #3

“Most people believe that COVID-19 was not grown in the lab, so it must be true.”

Example #4

“Most people believe that COVID-19 was grown in the lab, so it must be true.”

Explanation: In each of the four examples, you can see that the claim is based on popular opinion. The claims have nothing to do with how the actual world is, but they instead appeal to the people who endorse the claims. Each claim is based on popular opinion, but that doesn’t help us get to the truth. These are examples of bad arguments.

Appeal to Popularity in Marketing

Psychologists have long known that group thinking is one of the key components in the decision-making process. From the early 20th century, New York advertisers used appeal to popularity as a tactic to persuade groups of people to buy their products: “We are the number one seller of x, so we are the best.”

How to Disarm the Appeal to Popularity

The way to counter the appeal to popularity is to explain that the majority can be wrong. It helps to have a clear example that illustrates this. For example, at one time everyone believed that the sun orbited the earth, but it turned out that everyone was wrong.

What Should You Do Instead?

A wisdom seeker is interested in knowing and understanding what’s true. To avoid falling for the appeal to popularity, wisdom seekers understand that for critical thinking, they take the source of the claim out of consideration and only focus on the claim itself. The evidence given with any particular claim helps a wisdom seeker decide to either accept, reject, or withhold judgment on any claim.