Appeal to Authority Fallacy: How to Avoid It

My friend Gullible and I were having a discussion:

Gullible: “I heard from Andrew Yang that universal income is the best solution to fight poverty.”

Me: “Why do you believe that?”

Gullible: “Yang is successful and famous, so he must be right.”

This is a common informal fallacy called “The appeal to authority.”

What Is an Appeal to Authority Fallacy?

Appeal to authority arguments look to support a claim by appeal to the person who’s making the claim. Since claims are true or false regardless of who makes them, the person who’s making the claim is irrelevant to evaluating the claim’s truth or falsity. That’s why appeal to authority is categorized among the fallacies of relevance: it appeals to irrelevant information in an effort to get people to endorse a claim.

For example, if Einstein claims that happy marriage starts when you marry your first love, that doesn’t automatically make the claim true. Einstein was a genius physicist, but that doesn’t mean everything he says is true. Accepting a claim simply because of who’s saying it is a fallacy: a person’s say-so doesn’t show that the claim is true. The truth or falsity of a claim is completely independent of the person who makes it.

Some other names for the appeal to authority are “Argument from authority,” “Argumentum ad verecundiam,” and “Ipse dixit.” It’s a common fallacy of relevance like a genetic fallacy, straw man fallacy, or appeal to popularity.

Here’s what appeal to authority looks like:

“We should all make climate change our number-one priority because Leonardo DiCaprio said so.”

This is a logical fallacy because hearing a claim from a famous movie star doesn’t make the claim true.

Appeal to authority is different from relying on expert opinion. We obviously need to rely on expert opinion in some cases. If you want to understand what’s wrong with your car, you need to consult a mechanic. If you want to understand your taxes, you need to consult an accountant. If you want to understand something about the COVID-19 pandemic, you need to start with a virologist. But even experts can be wrong. Anybody can have false beliefs, and experts are no different.

Expert knowledge is limited by the expert’s area of expertise. For example, if you need to understand heart health, you’d want to start with a specialist in cardiology. They would have scientific evidence based on medical records to back up their claims. But if you want to understand mental health, a specialist in cardiology will have limited knowledge on the subject.

The appeal to authority fallacy is at work when someone uses the words of an expert in one domain to provide evidence for a claim in some other domain. The Einstein example illustrates this. Einstein was an expert in physics—a true authority figure in that domain. If Einstein said something about physics, that would give you some reason to think it was true; he was an expert in that domain. But he wasn’t an expert on marriage. To take his say-so as evidence in this other domain would be to appeal to an irrelevant authority—a false authority. It would be to commit an appeal to authority fallacy.

Appeal to Authority as the Mirror Image of Ad Hominem

Appeal to authority is often a mirror image of ad hominem. In an appeal to authority, someone appeals to the positive characteristics of a person to accept a claim, and in ad hominem, someone appeals to negative characteristics of a person to reject a claim. Both appeals are fallacious because the characteristics of the person are irrelevant to whether the person’s claim is true.

Appeal to Authority

Sam says there is an afterlife.

Sam is a saint.

So, there is an afterlife.

Ad Hominem

Sam says that there is an afterlife.

Sam is a devil.

So, there is no afterlife.

Contrast the earlier Einstein example with another: if Hitler claims that 2 +2 =4, that doesn’t automatically make the claim false. People with positive characteristics can still be wrong, and people with negative characteristics can still be right, so discussing personal characteristics instead of the claim itself is a fallacy.

Here are some examples of appeal to authority:

Example #1

Person A: “Appeal to authority is the weakest form of argument.”

Person B: “Why do you think that?”

Person A: “Aristotle said so.”

Explanation: Person A is appealing to Aristotle to prove that appeal to authority is the weakest form of argument. Appeal to authority is in fact among the weakest forms of argument, but the reason it’s weak isn’t that Aristotle said so. The reason it’s weak is that saying something doesn’t make it true—not even if it’s Aristotle who said it. Aristotle was the father of formal logic. He was the first to try to give an account of a valid argument, and the first to provide a system for identifying logical form, but that doesn’t mean that everything he says is true.

Example #2

“The Pope said we should not use contraception. Since the Pope is a religious authority, it must be true.”

Explanation: It is a fallacious argument to believe a person instead of evaluating his claim about contraception. If the Pope’s claim is true, it’s not true simply because he says so.

Example #3

“According to Planned Parenthood, women should have the ability to choose abortion. Since it’s Planned Parenthood, it must be right.”

Explanation: You can’t accept the claim simply because Planned Parenthood said it. They could be right or wrong, but we can’t accept their claim simply because they provide reproductive health care. If their claim is true, it’s not true simply because they say so.

Example #4

“Michael Jordan said that for fitness, we should make it mandatory for all children in school to play basketball. Since Michael Jordan was a great basketball player, it must be true.”

Explanation: You can’t accept a claim simply because it’s Jordan. The claim about making basketball mandatory for all children for fitness needs to be evaluated before accepting, rejecting, or withholding judgment about the conclusion. If Jordan’s claim is true, it’s not true simply because he says so.

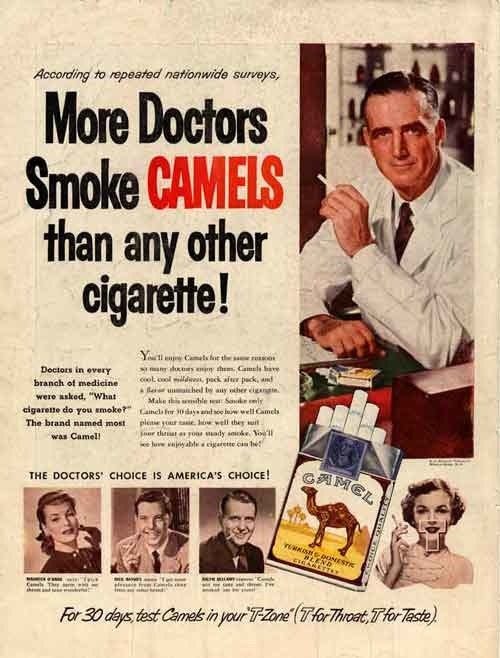

Appeal to Authority in Advertising

Advertisers have long used appeal to authority to promote their products. They understand that the public can jump on the bandwagon knowing an authority approves their product. Trident Gum used this well-known example:

“Four out of five dentists surveyed recommend sugarless gums for their patients who chew gum.”

Likewise, Wheaties used a similar ad featuring Michael Jordan. Its message: Wheaties is the best way to start the day because Michael Jordan eats Wheaties for breakfast.

Here’s an example of a New York Ad agency using doctors to sell cigarettes:

“More doctors smoke Camels than any other cigarette!”

How to Disarm Appeal to Authority

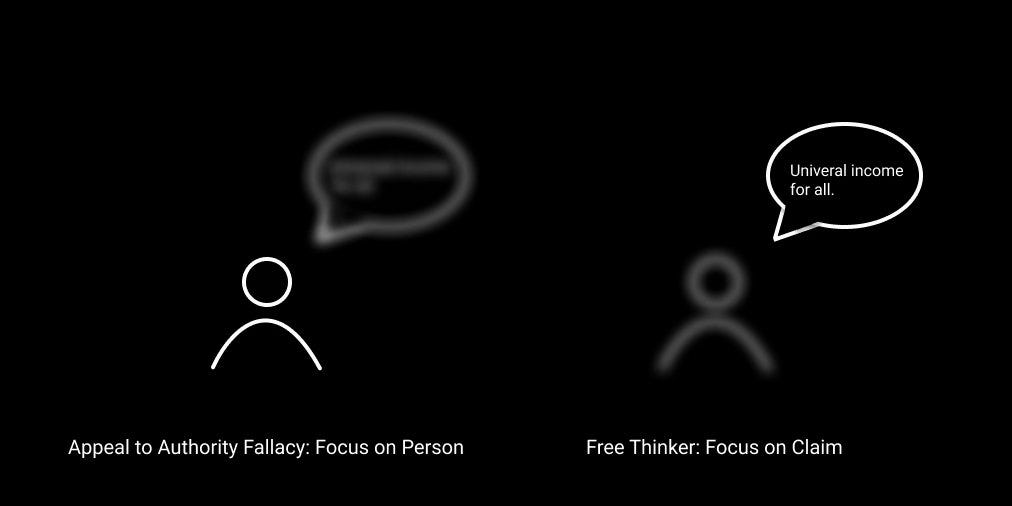

Most of the time, people appeal to authority in argumentation because it’s easy. It takes critical thinking skills to argue for or against an argument or claim, and most people aren’t skilled at doing that, so they fall back on something that’s more familiar, easy, and comfortable: evaluating people instead of arguments and claims.

If someone accepts a claim because of who said it, then point out that the claim still needs to be evaluated before accepting it. By focusing attention back on the claim, you’re bringing the fallacy to light and bringing the discussion back to where it belongs: the evidence in support of the claim.

Wisdom Seeker Approach to Appeal to Authority

Wisdom seekers are interested in knowing and understanding what’s true, and they are interested in the evidence, not only the source. In every case, the claim needs to be evaluated, not the person who makes it.

In general, you need to completely remove the person who’s making the claim from your evaluation of the claim. This is the only way to avoid an appeal to authority fallacy and ensure that you’re genuinely focused on knowing and understanding what’s true.